Based on feedback from my last article, I decided to revisit the question of “What is fair?” when it comes to the retirement plan fees being assessed at the participant level. I will begin with a brief recap of points made in my previous article, Fees: What everyone is NOT talking about, dated July 12, 2013.

Recap: When it comes to fees paid by participants, what is fair?

Should the fees be a level percentage of each participant’s account, should they be a level fixed-dollar amount per participant account, or should they be a combination of these two options? Plan sponsors have to make a choice. In fact, as fiduciaries they have an obligation of prudence in determining how fees are allocated to participants.

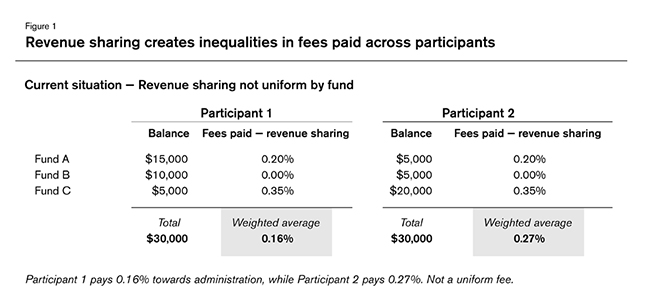

The first hurdle: Evaluation. Who is paying what at the fund and participant levels, including the fees paid via the revenue sharing arrangements embedded in a fund’s expense ratios? Sponsors will quickly learn that, because revenue sharing rates vary by fund, fees paid across participants are not uniform. There are several fee collection methods used today that cause these inequitable allocations (which is addressed later in this article). An illustration of how revenue sharing variations create inequitable administrative fees across participants based solely on their investment elections is demonstrated in Figure 1.

There are solutions to the variation in fees paid due to the fluctuation in revenue sharing rates. These solutions include: (1) using only institutional funds, (2) crediting the revenue sharing back to the participants on a fund-by-fund basis, or (3) using the revenue sharing as a fee offset on a fund-by-fund basis.

Once revenue sharing is normalized, then sponsors/fiduciaries can shift attention toward determining the appropriate allocation method (i.e., a prudent fee allocation policy). Based on their demographics, sponsors determine which fees should be paid by the participants and how they should be allocated (pro rata, per capita, or some combination). Later in this article, I will show the impact of these decisions on small balances versus larger balances within a plan.

As these discussions progress, along with the additional fee transparency, the marketplace will evolve hopefully to provide sponsors, plan fiduciaries, and participants with a clearer picture of the fees they pay and how they relate to services provided.

At the participant level , what is the disparity of revenue sharing?

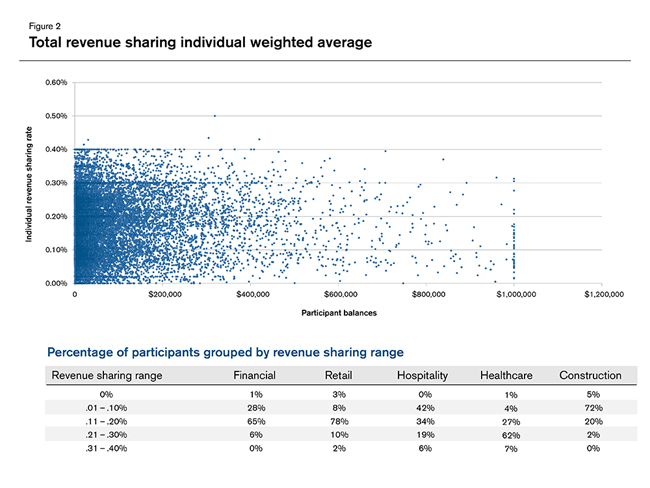

At this point, I think it is blatantly clear that revenue sharing creates disparity in fees paid across participants. But how much disparity truly exists? From time to time, I hear sponsors comment that most of their funds have revenue sharing and the rates are pretty similar, so each participant should be paying a similar fee. To test this assumption, I pulled participant data across five industry segments and calculated the participant-level revenue sharing by multiplying each participant’s fund balance by the revenue sharing percentage for that fund. I then summed the total revenue sharing generated across all funds for that participant and divided the total revenue sharing amount by the total account balance for an individual revenue sharing percentage. Figure 2 illustrates the graphical and tabular results of my findings.

As you can see in Figures 1 and 2, there is a large disparity in the amount of revenue sharing collected across the participant base. While I agree that a bell curve exists in which a large portion of the participants pay between 0.11% and 0.20%, think about this at that individual participant level. You may be paying 0.10% in revenue sharing to cover fees while your coworker may be paying 0.20%—twice as much for the same service.

It should be noted that most of the participant data used in the above analysis came from plans with normalized fee structures, meaning the revenue sharing paid is netted against a fixed fee, so everyone pays a uniform rate regardless of their individual revenue sharing percentages. The chart above illustrates individual revenue sharing as if the fees were not normalized. In addition, all of the sample data came from plans with model portfolios. These two characteristics most likely reduced the disparity levels across participants. Anecdotally, absent these characteristics, I believe we would have seen more disparity and a larger percentage of participants at a zero individual revenue sharing percentage.

Which fee collection methods are not fair?

In my first article, I noted that—within the industry today—there are a number of fee collection methods which create inequitable fees at the participant level. Although these methods may be obvious to some, it may be worthwhile to dig a little deeper and review some of the more common fee collection methods used today, which create nonuniform fee allocations across participants.

Method 1: Revenue sharing only . This means no explicit fees are paid from the plan. The revenue sharing generated by each fund, in total, provides enough total revenue to cover the administrative fees. Not only are these revenue-sharing-only fees not equitable, they really are not very transparent. Let’s face it, most employees (and some sponsors) don’t realize the impact these embedded expense ratio fees have on their account portfolio growth. While the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) mandated that the total expense ratio be expressed as a percentage and as a dollar amount per $1,000 invested, it did not require the revenue sharing portion to be detailed on the participant fee notice or statements. The required disclosure is to simply say, “Some or all of the plan’s expenses may be covered by the investment expense ratio.”

Under this method, fiduciaries need to be very careful that the fees paid are reasonable relative to the services provided (not the cheapest, but reasonable for the services provided). In my mind, this approach is the hardest for plan fiduciaries to monitor to ensure that their fees are in-check.

There have been recent court cases (e.g., Jerome Schlichter cases) where sponsors have been ordered to make restitution to the plan for excess fees embedded in their funds’ expense ratios (i.e., too much revenue sharing). Bottom line, sponsors need to keep a handle on revenue sharing and other implicit fees!

Method 2: Revenue sharing used as a fee offset . Under this method, the revenue sharing amounts collected are not enough to cover all of the fees. The total fees are calculated and then reduced by the revenue sharing collected. Because there is no net offset at the fund level, the same inequitable fee arrangements exist with participants paying a nonuniform rate in fees. The remaining fees not covered by revenue sharing can be paid by the employer or allocated to the plan.

An interesting consideration under this method is when the employer pays the remaining fees. The revenue sharing payments are deducted from the total amount due, leaving a net amount for the employer to pay. Think about it—the employer has control over the amount of the check it cuts based on their investment selections within the plan. I am not saying this is necessarily wrong. However, in today’s environment, the perception definitely could be that the employer is picking funds with higher revenue sharing to lessen the amount of the check they cut. I realize that the counterargument is that the employer was generous enough to pay some of the bill versus charging it back to the plan. Nevertheless, this is all the more reason to adopt a fee policy that neutralizes the disparity of revenue sharing and creates a uniform fee across all participants.

Method 3: ERISA accounts. Under this method, the revenue sharing amounts are collected from the funds and deposited into a holding account within the trust. As plan expenses arise, they are deducted or paid from the ERISA account. The good thing about ERISA accounts is that all the money movements between revenue sharing and expenses are handled at the trust level, creating a good audit trail. But the same issue still exists in that funding the ERISA account from revenue sharing (which varies by fund) results in fees paid by the participants not being uniform.

The DOL recently issued Advisory Opinion 2013-03A, which clarified some questions as to whether revenue sharing payment should be considered a plan asset, but it did not delve into the problem of generating nonuniform payments across participants. Conversely, it actually created more questions for lawyers to contemplate.

Correction of revenue sharing disparity is not perfect

Any fee arrangement that involves revenue sharing in which the revenue sharing is not applied on a fund-by-fund basis will create nonuniform fee allocations across plan participants. Although there are methods, as discussed in my previous article, that can normalize fees, allowing all participants to pay a uniform fee, there are inherent administrative issues that prevent some of these methods from being completely accurate.

Remember, back in the '80s and '90s, the big push to daily recordkeeping from the balance-forward accounting method? One of the primary reasons for the change was because the earning allocations in balance-forward plans were formula-driven at the fund level, based on assumed cash flows during the accounting period. In other words, the earnings credited to each participant account were not exact because the earnings allocation was formula-driven, based on assumed cash flows/timing during the accounting period. Well, the same allocation issues can exist with the crediting of revenue sharing because the formula and timing used by the fund company to calculate the revenue sharing does not correspond with the allocation methods used when the actual revenue sharing dollars are credited back.

For example, assume revenue sharing is paid by the fund company monthly or quarterly and the fee normalization method chosen by the plan sponsor is to allocate all revenue sharing back to the originating fund. Once paid, the revenue sharing will most likely be allocated across current balances, which are often similar to the balances used by the fund company to calculate the revenue sharing amounts, but not exact matches. Unless revenue sharing is accrued daily the way dividends are, the actual allocation of revenue sharing amounts will never completely align with the original calculations used to determine the amounts.

In a nutshell, revenue sharing really creates a mess. It is not a uniform fee when left alone and when it is normalized, the end results are still not completely accurate. Albeit not perfect, from my perspective, the normalization of revenue/fees to participants is still more accurate than doing nothing.

What impact do per capita fees have on the proportion of fees paid between low and high account balances?

In my first article, I discussed how plan sponsors have a choice when deciding how plan fees are paid by plan participants. That is, (1) fees can be allocated across participants based on account balance (uniform percentage), or (2) they can be paid per capita (uniform dollar amount), or (3) a combination of the two methods.

When fees are assessed as a percentage of a participant’s account balance, it is simple math—lower account balances pay less in fees on a dollar basis and larger account balances pay more. The inverse is true for per capita fees in that the fees are a consistent dollar amount across participants. However, when expressed as a percentage of the balance, we see variations. Yet if a combination approach is used, how much of the fees are actually shifted from higher account balances to lower account balances, because a portion of the fees is per capita?

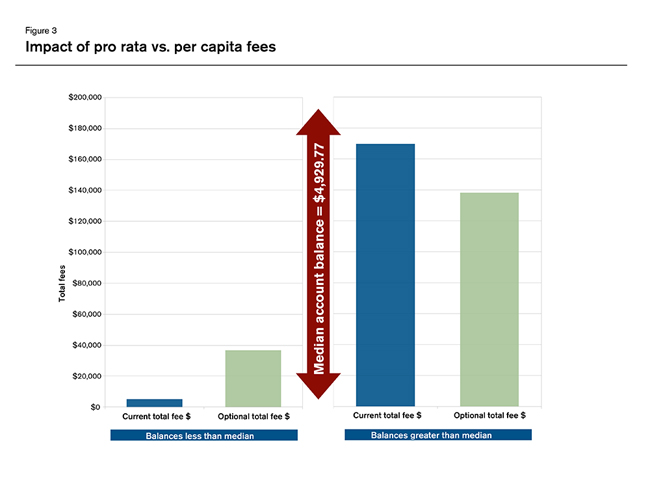

Figure 3 shows an actual exhibit I prepared for a client who was contemplating assessing fees from participants on a per capita basis.

Median Account

For this illustration, I divided the participants based on the plan’s median account balance so there was an equal number of participants represented by each side of the bar columns. Adding the blue columns together, the total fees are about $175,000, with the participants above the median plan account balance paying around $170,000 and the remaining $5,000 fee paid by the lower account balances. I then took the same total fee of $175,000 and first allocated a fixed per capita fee of $36 per participant (annually) with the remainder of the fee allocated per capita. The result: the smaller account balances paid approximately $37,000 in fees, with the higher balances paying $138,000.

Which allocation method to use is the plan sponsor’s choice and conversations typically are based on how each allocation formula will impact the various segments of the participant population. There is no “one size fits all.” However, I think the analysis illustrated above is interesting in that the total fees paid by lower account balances (representing one-half of the participant population) were still a fraction of the total fees paid by the higher balances even after a partial per capita fee. Of course, the demographics of each plan will produce different results.

Conclusions

I envision that over the coming years, additional discussions within retirement committees about creating a uniform and fair fee structure that “fits” their employee populations and cultures. Plans that have revenue sharing should consider “normalizing” these payments. Even though the methods utilized are not perfect, they still create a more level playing field for participants.

Advisers and consultants should lead their clients in these discussions while practitioners adhering to the old practices need to embrace new ideas. The idea of fixed fees, uniform rates, and fair allocation policies should lead to more transparency and better alignment of services for the fees paid, ultimately resulting in a “win-win” for those who tackle this next obstacle within the defined contribution retirement industry.